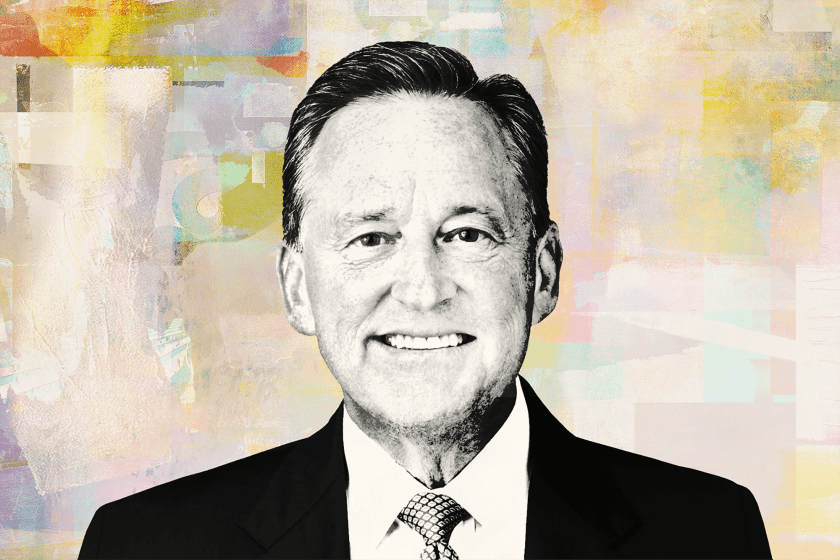

Andre Bouchard had an eventful seven years as Chancellor of the Delaware Court of Chancery. In Part One of The Deal’s extended interview with The Deal’s David Marcus, Bouchard described the significance and aftermath of his 2016 decision in a case arising from the sale of Trulia Inc., which put a stop to a pervasive form of shareholder litigation challenging M&A transactions.

In Part Two below, Bouchard explains the thinking behind his decision to lobby for the addition of two judges to Chancery in 2018, the first time the court had been expanded in almost 30 years. He also shares his thoughts about professional life at Paul, Weiss, Rifkind, Wharton & Garrison LLP, which he joined as a partner some 10 months after announcing his retirement from the bench on Dec. 29, 2019.

Sign in to TheDeal.com for Part 1 of our extended interview: “Bouchard Looks Back at Trulia”

Expanding the Court

The Deal: You were a prime mover in expanding the Court of Chancery, from five to seven judges. How much of a change has that made in the court’s workload, which it seemed like was absolutely crushing before that expansion?

Bouchard: It definitely helped to expand the court and get the two new judges, no question about it. But if you build it, they’ll come. People kept coming. It has been, I don’t know if I could say equally busy, but consistently busy since. There’s been no let-up. I was Chancellor for seven years, starting in 2014 and going until May 2021. The new judges came in in the latter part of 2018. I would say it was really off the charts busy in those first four years. But it was almost equally busy, and by the end equally busy, afterwards.

I think it’s worth talking about what’s going on here. When we asked for the new judges in 2017, we did a needs analysis, and there were some key things we found. Number one, there had not been a new judge on the Court of Chancery since 1989. Number two, all the metrics were going up. The number of filings was going up, the number of pages that judges were being asked to read was going up, the number of motions was going up, the number of cases seeking expedition was going through the roof, and so forth.

But there was also a more fundamental phenomenon that until you looked at it in an organized way may have escaped a lot of people’s attention. The case mix was changing in the Court of Chancery. If you look back 25 or 30 years, the case mix in in the Court of Chancery was 80% or 85% corporate governance cases, and the other 15% was local property disputes, guardianship cases, and the rest of the docket.

Today, or even in the last 10 years, the mix is much more balanced between corporate governance cases and pure commercial cases. By commercial I mean not internal affairs or corporate governance, but typically a contractual relationship. The reality of the corporate cases is that when you have personal liability in the mix, they tend to settle when you get beyond a motion to dismiss.

When you’re in a pure commercial case, those are economic bets — it could be a purchase price adjustment, it could be an earn-out — where you’re saying, it will cost us this much to litigate but here’s the potential benefit if we recover something. The commercial cases tend to involve more discovery because they don’t settle as early. They tend to involve more motion practice. They tend to go to trial more often. The burdens associated with commercial cases can be more extreme than the typical corporate governance case.

The underlying reason that mix was changing in large part was the rise of alternative entities. The LLC Act was enacted in Delaware in 1992. If you look in the late 1980s, before the LLC Act, Delaware had about 200,000 entities. Today, Delaware has about 1.7 million entities. Think about that. In most courts, like a normal civil court, you would think about needs in terms of population. How many citizens do you have? How many crimes get committed, how many slip-and-falls, how many car accidents, how many medical malpractice cases do you have?

The population the Court of Chancery primarily served during this period exploded eight- or nine-fold, and a lot of that was due to LLCs from the LLC statute being enacted in 1992. I can’t give you the exact breakdown, but I would say probably 80% of that 1.7 million entities, maybe 70%, are alternative entities.

What does that mean? Among other things, it means largely contractual kinds of issues that you’re facing, because you have the ability to eliminate fiduciary duties, then the issues can be very bespoke, very contractual in nature. Those kinds of cases typically put more pressures on the docket in the way I described earlier. That’s a profound change that has put the court in high demand. It’s a good thing we’re in demand, but it does tax resources.

What do you see as the biggest challenges for Delaware as a center of corporate law over the next five to 10 years?

A significant challenge is consistently getting talent on the Court of Chancery. Regrettably, the disparity between the economic return for somebody to go into private practice and to be a judge for a period of time are so vast today, much more so than 30 years ago, that you don’t see as many people who have practiced for 20 or 25 years apply to go onto the bench. We are so lucky we have the people we have, and they’re all exceptional. My biggest concern is continuing to have exceptional people on the court.

The body of corporate law precedent the Court has is unique, it’s wonderful. We have this 100-year body of precedent behind us where Delaware has been preeminent. The reason people in my judgment want to litigate in the Court of Chancery is that business people and investors like predictability. I think the predictability factor of litigating in the Court of Chancery is as good as exists in the context of business litigation. But the only thing that makes that work is having good people being in the position of judging cases. So that’s my greatest concern.

Joining Paul Weiss

The seats on the Court of Chancery have a 12-year term. You stepped down after seven years. Why did you retire from the bench when you did?

I turned 60 years old in January. I had been litigating or on the bench for 35 years, working at a very intense level. I had only a certain amount of time left in my career. I had done everything on the Court of Chancery I wanted to do, and I wanted to take some time off, relax, and take stock to see what I would enjoy doing next. After taking a break for about five months, which was perfect for me, I decided I didn’t want to be done with the legal business, but that I’d like to play a different role than what I had been doing for 35 years, to have a more senior, advisory role.

What was your thought process once you made that decision, and how did you end up at Paul Weiss?

After I left the bench, a number of people called me, people from Delaware, people like Paul Weiss from around the country. Even before I was planning to talk to people, it was happening, but that’s okay. I was very fortunate that people wanted to talk to me.

The culture of Paul Weiss is very special. I got to know many people here through an extensive interview process. I think I met something like 70 different partners. I also had seen many of their litigators who appeared in front of me, and I was uniformly impressed with the quality of their work and how they approached matters in the Court of Chancery. I was extremely impressed with the clientele that Paul Weiss has and the resources it has.

It was a natural fit. Stephen Lamb was at one time my partner briefly before he went on the Court of Chancery. We had a boutique firm together, Lamb & Bouchard. Steve had been with Paul Weiss and that mattered a lot to me, because he had a wonderful experience here, and my experience has been equally wonderful. It was just a good fit for me. I’m sure I would have been happy at any number of places but this fit has been spectacular for me.

I’m amazed by the people here and the work they do. Paul Weiss also has embraced a lot of people who have been active in public service, Loretta Lynch and Jeh Johnson being two examples of people who went into high-level positions in the federal government and had Paul Weiss roots or came back to Paul Weiss. I’m a big believer in public service and a firm that embraces that warmed my heart.

How do you envision your practice at Paul Weiss?

I think the headline words would be advisory in nature. The things I would like to be doing would involve interaction with boards, with committees, special committees, demand committees, special litigation committees, and investigative types of things. I also will stay active on a strategic advisory level behind-the-scenes on litigation matters. I have had extensive experience in that area both in the context of derivative and class action cases. And I would enjoy advising on corporate governance and compliance issues with boards or with managers in whatever opportunity may arise. That could be in the transactional space. I’m already starting to field calls that come up in all sorts of contexts that I never envisioned.

Editor’s note: The original version of this article was published earlier on The Deal’s premium subscription website. For access, log in to TheDeal.com or use the form below to request a free trial.