Corporations have come to realize that every company needs to be a technology company or a technology-enabled company.

As a result, M&A strategies have become more focused on acquiring and integrating technology enterprises, a process that is not without its challenges for old-guard institutions.

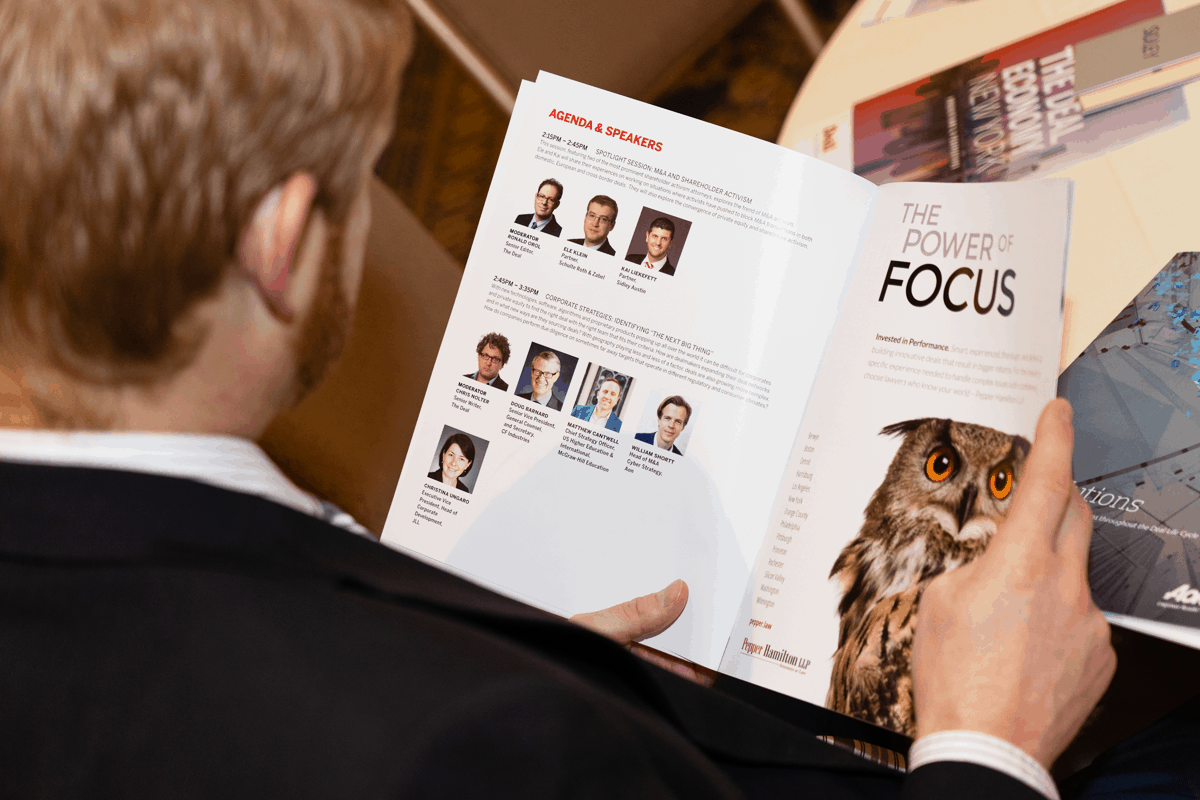

Companies in industries ranging from real estate to agriculture to education are grappling with these issues, according to a panel of experts speaking Wednesday, Nov. 20, at The Deal Economy Conference in New York.

What often comes first for many public companies considering how to address a growing technology need is determining whether or not they would be better served by investing in the internal development of a proprietary technology or by investing in an acquisition.

“When we look at a technology acquisition, we definitely do a build analysis, and that tends to be a theoreticals-on paper-driven exercise, ” Jones Lang LaSalle Inc. (JLL) executive vice president and head of corporate development Christina Ungaro said. “More often than not we end up going the acquisition route, because we tend to underestimate the time and cost of talent that’s really going to be needed to build a viable product and get us there quickly.”

The reality is, as Ungaro explained, that large public companies face more difficulty than private capital-backed ventures to build technology because there is a lot less tolerance for failure, and the luxury of having the time and capital for trial and error is hard to come by.

But the challenges are certainly not in the rear-view mirror once a company opts to go the acquisition route.

“It’s especially difficult to do due diligence and successfully integrate tech acquisitions,” CF Industries Holdings Inc. general counsel Doug Barnard opined, pointing to HP Inc.’s (HP) $10.8 billion acquisition of Autonomy Corp. in August 2011. “They paid over $10 billion dollars for it, they performed very extensive due diligence, less than a year later they wrote off some $6 billion or $8 billion of their acquisition price because they missed some critical problems during due diligence.”

What can also be extremely complicated when acquiring a technology company is merging cultures, which may often be “free-wheeling,” and the “polar opposite of the culture you need to operate to be successful in a large multinational,” according to Barnard.

As for how to tackle that challenge, the jury is still out.

“From the feedback I’ve heard from clients, it’s best when you acquire a technology firm not to do anything, basically,” Aon plc (AON) head of cyber strategy M&A William Short said. “The culture is unique. You are dealing with extremely creative people — coders or artists — and they’re best left to continue on with what they’re doing and doing well.”

Recent sexual harassment scandals and other cultural issues at tech-focused companies such as Uber Technologies Inc. (UBER) and Alphabet Inc.’s (GOOGL) Google may make that strategy a tough pill to swallow for conservative corporate buyers.

McGraw-Hill Education Inc. chief strategy officer Matthew Cantwell said when his company acquired Aleks Corp. in 2013, the last thing it wanted to do was stifle their target’s creative culture.

“We acquired them and we integrated them but we gave them the autonomy they need to continue to innovate,” he said. “They have their own email addresses, they have the office in Southern California, they have the foosball table, and I think we have done a good job of mixing them into a multinational corporate publishing culture without diluting their capabilities.

One thing is certain, though. As long as technology companies continue to come up with solutions for the problems of centuries-old industries, the market players in those industries will continue to wrestle with the idea of how best access that solution.

“There’s a startup in Boston with $200 million in seed capital from [Bayer AG (BAYN)]; they have genetically modified organisms they’re trying to develop that would allow corn to get nitrogen from the atmosphere,” Barnard, whose company distributes nitrogen-based agricultural fertilizers, said. “That’s the product we produce, so as we think about that substitute product, if you will, defensively, we wonder if we should be investing ourselves in companies like that and be thinking about them as potential acquisitions when they’re more mature.”

Editor’s note: The original version of this article was published earlier on The Deal’s premium subscription website. For access, log in to TheDeal.com or use the form below to request a free trial.

This Content is Only for The Deal Subscribers

If you’re already a subscriber, log in to view this article here.