Family office managers and private equity general partners have many common interests. Chief among them is providing maximum returns for their employees and their investors.

How family offices and private equity funds achieve these objectives does not always line up perfectly, however.

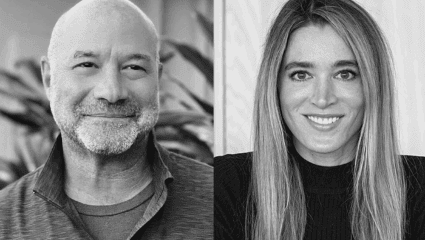

In a recent interview with The Deal, Pepper Hamilton LLP partners Julie Corelli and Irwin Latner suggested that it takes a certain level of sophistication for family offices to invest in private equity, and before becoming involved in this asset class, family office managers should be aware of a number of red flags that often pop up.

“A private equity fund has an investment period and a harvesting period, and then you wind down the fund at the end of the investment period,” Corelli said. “They start up with a new fundraise and they go on and on. So, there is an absolute mandatory exit in there, and that’s probably the biggest flaw in the model for family offices.”

For certain investments, such as those with yield, a family office may be far more interested in maintaining ownership for as much as 20 or 25 years, Corelli explained.

“So the term aspect of PE investing is certainly a place that family offices and the private equity model don’t match up well,” she said.

Other sticking points for family offices include potential affiliate and operating partner conflicts, cybersecurity risks, governance issues, succession planning and use of leverage, according to Latner.

“I think family offices may not always be very sophisticated so as private equity investors, they should be cognizant of that,” he said. “All due diligence issues may not be obvious just from reading the fund documents.”

Corelli and Latner’s comments come as the Securities and Exchange Commission continues to increase its scrutiny on private equity fund managers for expense allocation practices, consulting and advisory fee acceleration, unauthorized agency and affiliate transactions, inflated valuations, investor reporting, compliance and other issues.

In July, the SEC settled proceedings against a North Brunswick, N.J.-based portfolio manager for mispricing private fund investments, resulting in a large personal bonus of $600,000 for the manager and exorbitant fees paid by the fund.

Similar cases have cropped up in the news in recent months, and Corelli finds in their wake that transparency in affiliate transactions and fee and expense allocations are among the greatest concerns for family offices when it comes to SEC enforcement of private equity.

It’s important for family offices to realize that, statistically speaking, the percentage of examinations into private equity that progress to enforcement by the SEC is very low, and those that do go that far are often the most egregious cases, she said.

“We don’t see the examination contexts in the public record,” Corelli explained. “You have to talk to people who are experienced in having seen what’s there to know what to do with it in the fund documents and to advise the family office on what to look for there when it comes to the allocation of expenses, what shows up in deficiency letters from examinations, the way to deal with conflicts and how to cleanse them and what a family office should encourage the fund manager to do to cleanse of conflict.”

Other recent enforcement actions from the SEC have focused on portfolio company fees and compensation, such as a failure to properly disclose how managers are compensated for portfolio company transactions or what types of broken-deal or co-investment expenses are included in these deals, according to Latner.

“These are the types of things that private equity managers themselves are becoming more and more focused on,” he opined. “I think a sophisticated or knowledgeable family office investor should focus on these things as well.”

All these concerns to keep track of may cause family offices to consider avoiding private equity altogether.

While Corelli and Latner agree that there are ways to navigate this investing platform successfully for family offices, they offered several other options available for those who lack the resources or level of sophistication to take the risk of diving into private equity.

Family offices may decide to explore so-called independent sponsor or pledge-fund models, through which they can invest on a deal-by-deal basis. This gives the investors a type of umbrella fund with pre-agreed upon structure and economic terms and spells out how they can opt in or out of specific deals.

One structure the advisers frequently field questions on are permanent capital vehicles, or PCVs, which are investment vehicles created directly by family offices that have perpetual investment horizons and have different buckets for different types of assets, such as fixed income, private equity, real estate, hedge funds, or anything that family offices may see as opportunistic.

“Family offices can have any number of buckets of strategies, and they may roll those up into a single platform for the family,” Corelli said. “It’s very easy to fit these within the family office exemption and do that for the family investors.”

Of course, if family offices start to take in third party money, they must be cognizant of the $150 million exemption threshold, after which they would be considering registering with the SEC as an investment advisor.

“You want to grow the business, and at this point, you’re looking for more and more models that fit what the family wants to do and what third party investors want,” Corelli said. “That’s where I think permanent capital vehicles have started to gain a good deal of traction. They are very bespoke.”

Whether you’re considering investing family capital in private equity funds or launching your own permanent capital vehicle, family offices should know what questions to ask and what buttons to push as they explore these various investment alternatives. According to Corelli and Latner, there are several educational resources available for family offices in this regard.

“The Institutional Limited Partners Association recently came out with a template LPA,” Latner said. “I think that’s a very good resource for family offices to become educated about private equity investing and understand where the inflection points are — what are the key terms when you’re comparing the template against the marketplace of all the general partner terms, how they’re changing a general partner’s fiduciary duty from best practice, etc.

“All of these things will provide a template for building a good way to do due diligence when preparing for private equity investing and explain how family offices should approach the growing market for secondary transactions and explore other possibilities.”