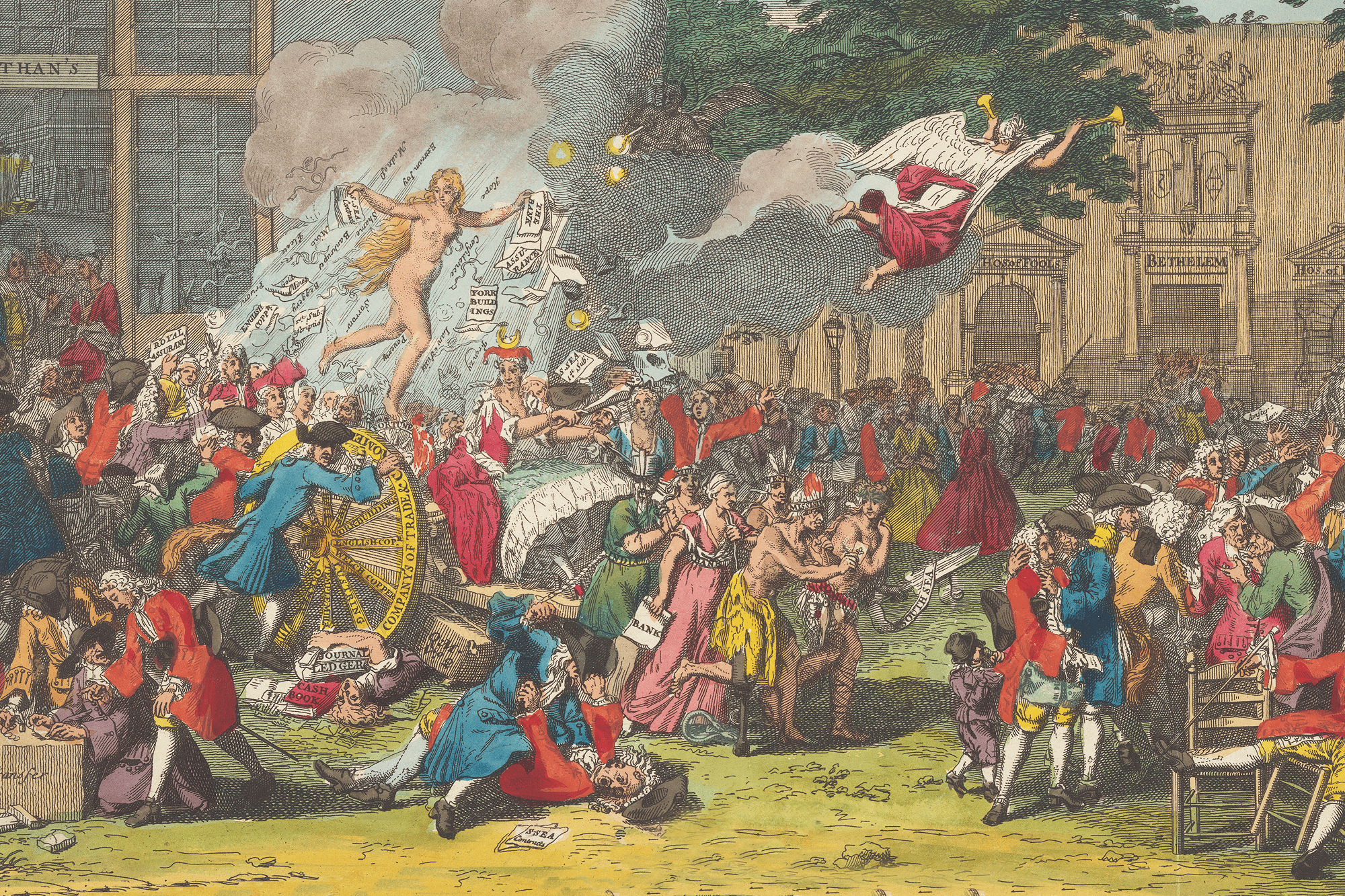

The 18th century prints teem with figures realistic, satirical and mythological. Crowds fight over papers floating down from above. Scatological images abound; in one of the more creative, a man with his pants down is force-fed coins through a funnel and discharges a long paper that reads “Laaaw,” which a man below carefully takes hold of. In another print, a man pops out of a small globe — a bubble — labeled “Mississippi” and waves a paper that reads, “How can I get out of this?”

Many investors in Paris, London and Amsterdam were tormented by the same question as they counted up their losses from the collapse of the Mississippi and South Sea Bubbles, which are the subject of an exhibition at New York Public Library’s Stephen A. Schwarzman Building entitled Fortune and Folly in 1720. The show was planned for 2020 but postponed because of the pandemic.

The collection of prints, books and objects from the NYPL explores “the world’s first international financial crash,” as co-curators Nina L. Dubin, Meredith Martin and Madeleine C. Viljoen call their subject in an accompanying pamphlet. The bubbles were a central episode in the development of modern finance, and the material in the show depicts how people at the time struggled to comprehend them.

The crash has remained a landmark in the history of finance; the NYPL has considerable material on it in part because of the fascination the events of 1720 have long held for financiers such as J.P. Morgan, who donated part of his collection of items on the bubbles to the NYPL.

“The 1720 crisis was a debt crisis, a currency crisis, a stock market crisis and a banking crisis,” said Trevor Jackson, a professor at George Washington University and author of the new book, “Impunity and Capitalism: The Afterlives of European Financial Crises, 1690-1830,” in an email.

“Modern finance had mostly been created by 1720, but the 1720 crisis showed that it could cause disasters, so it was the moment when people had to decide how much finance was good versus destructive and how it should be governed or regulated.”

The central figure in both the bubbles and the show is the ScotsmanJohn Law — or, in the print mentioned above, Laaaw. In 1705, he published “Money and Trade Considered: With a Proposal for Supplying the Nation With Money,” in which he argued that Scotland should create a system of paper money backed by land rather than by silver and gold, which underpinned the national currencies of the era. The Scottish government didn’t do that; instead, it opted to solve a debt crisis by unifying with England in 1707 to create Great Britain.

Law spent the next decade promoting his ideas around Europe, Jackson says, and found an audience in France, where in 1716 he established the Banque Générale, which had the power to issue notes — in effect, currency. The next year he created the Compagnie d’Occident, later renamed the Compagnie des Indes, which became popularly known as the Mississippi Company because it had the exclusive right to develop the French territories along the Mississippi River.

Law and the French government aggressively promoted the company’s economic prospects — which were to be enabled in part by the labor of enslaved Africans — and investors bid up its stock. Law then merged the Banque Générale with the Compagnie des Indes and allowed investors to purchase the company’s stock with state-issued securities that Law hoped to use to retire the considerable national debt created by Louis XIV, a strategy that led to a speculative frenzy.

In 1720 Law was made France’s minister of finance by the regent for King Louis XV, then a child. But the triumph was short-lived. Law tried to de-monetize gold and silver to force people to use his paper money, Jackson says, which caused a bank run and, in turn, the collapse of the bubble. Law was expelled from France, and he and his common-law wife, Lady Katherine Knollys, became widely ridiculed figures.

Daniel Defoe, now most famous for the 1719 novel, “Robinson Crusoe,” the next year came out with “The Chimera: or, The French Way of Paying National Debts, Laid Open,” in which he criticized Law’s creation of paper money. But Defoe was a propagandist for the South Sea Company in London, which followed a path similar to that of the Compagnie des Indes.

Formed in 1711 to manage England’s national debt, the South Sea Company was given the exclusive right to the slave trade in the “South Seas” and South America. The company never engaged in the slave trade to any significant decree because Spain controlled South America, but it promoted the economic possibilities of the trade, which helped drive demand for its stock.

Instead, during the 1710s the South Sea Company exchanged its stock for various forms of English national debt, which inspired increasingly fevered rounds of speculation. Even Sir Isaac Newton got sucked in. By March of 1719 the 76-year-old Newton owned £12,000 of South Sea stock that he apparently sold the next year at a tidy profit.

But he bought the stock again a few months later at twice the price and ended up losing most of his investment, Andrew Odlyzko, a mathematician at the University of Minnesota who has studied Newton’s investment in the company, said in an email. That was a common plight by December 1720, when the South Sea bubble had finally burst because, says Jackson, a Parliamentary investigation proved that the South Sea directors were promising dividends that were impossible because their project was built on bribes and insider trading. There is no evidence that Defoe knew about the fraud, Jackson says.

The mania extended to Amsterdam, a market that played a central role in moving money around Europe and one where investors bought stock in both the Mississippi and South Sea Companies, Jackson says. A group of Dutch printmakers marked the collapse by printing a collection of prints entitled “Het Groote Tafereel der Dwaasheid,” or “The Great Mirror of Folly,” from which many of the items in the NYPL’s show are drawn, including those of the man being force-fed coins and the one hoping to escape from the Mississippi bubble.

English printmakers adapted — or pirated — works that appeared in “The Great Mirror of Folly.” In one of the best known, a naked woman — Fortuna, or Fortune — dispenses to a crowd of people papers inscribed with the names of the British companies that rode the speculative wave along with the emotions that accompanied the boom and bust, including “extreme joy,” “sorrow,” “madness” and “poverty.”

Other English artists offered their own interpretations, including a young William Hogarth, who in “An Emblematical Print on the South Sea Scheme” showed a devil hacking Fortuna to pieces with a scythe and chucking them to a crowd. Hogarth would go on to become of the great English artists and social commentators of the 18th century.

The crash did have serious consequences for some of its perpetrators. John Aislabie, the chancellor of the exchequer in England when the South Sea Bubble burst, was imprisoned in the Tower of London for five months; the show includes an expense report that the Tower’s Constable made for costs relating to Aislabie’s stay.

Aislabie’s image appears in “A True Picture of the Famous Skreen Describ’d” in the London Journal No. 85, a print that shows both the opacity and the corruption of the government’s involvement in the South Sea bubble. The face on the screen is that of Robert Walpole, Aislablie’s successor as chancellor of the exchequer, who was nicknamed the Screenmaster General for his protection of political cronies. Aislabie is one of the three figures reflected in the mirror. But however dubious the action seems and however justified the suspicions of viewers might be, they can’t see what’s going on behind the screen.